Constantino, Renato, and Constantino, Letizia R. Excerpt from A History of the Philippines:

From the Spanish Colonization to the Second World War. New York and London: Monthly

Review Press, 2008 [1975]. 162-166.

[162]

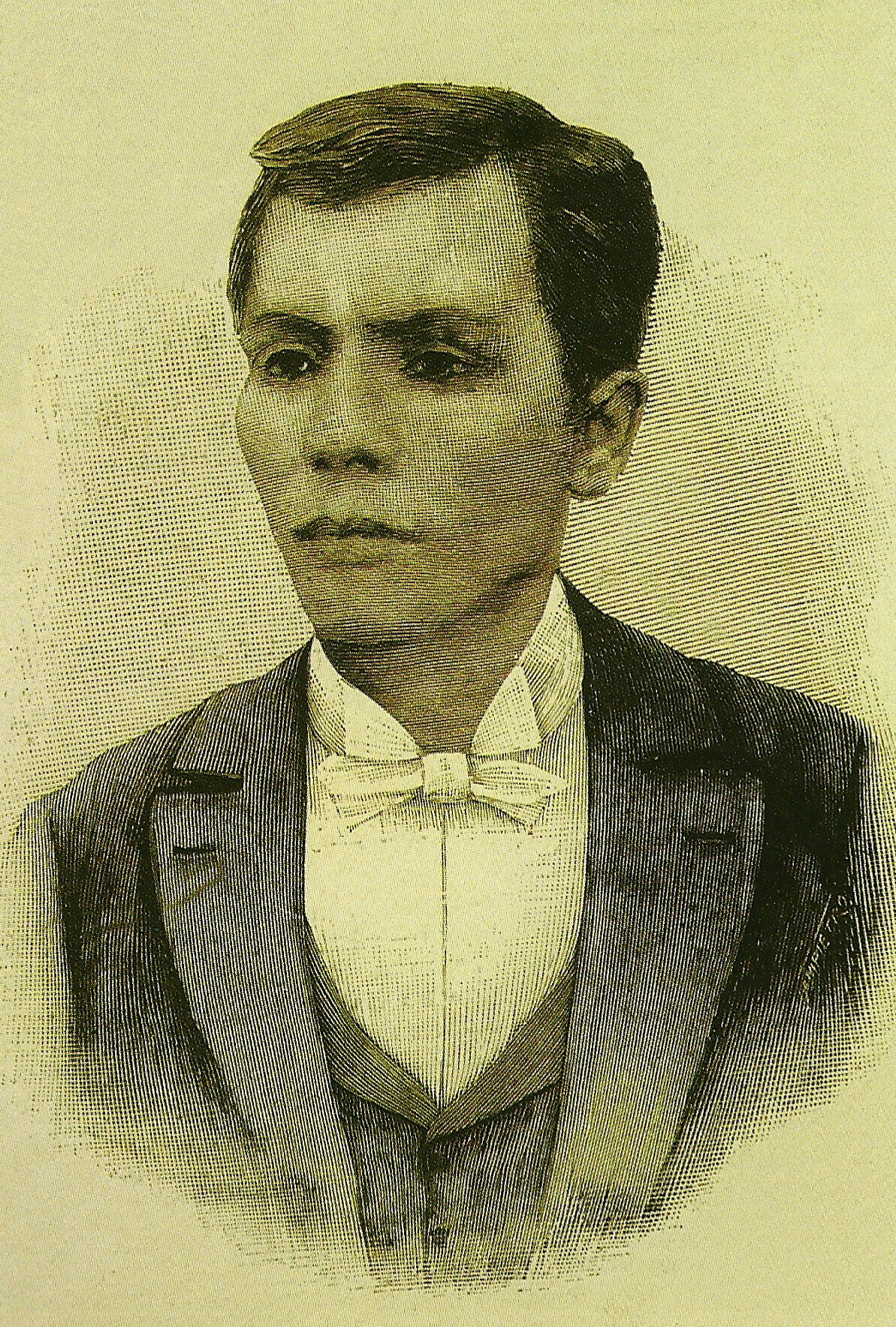

Bonifacio

Bonifacio’s own lower middle class origins may be gleaned from his biography. His mother was a Spanish mestiza who used to work as a cabecilla in a cigarette factory. His father, a tailor, had served as a teniente mayor of Tondo.26 Bonifacio was born in Tondo in 1863. The early death of his parents forced him to quit school in order to support his brothers and sisters. Bonifacio first earned his livelihood by making walking canes and paper fans which he himself peddled. Later, he worked as a messenger for Fleming and Co. and as a salesman of tar and other goods sold by the same firm. His last job before the Revolution was a bodeguero or warehouseman for Fressell and Company.

Read more »[162]

Bonifacio

Bonifacio’s own lower middle class origins may be gleaned from his biography. His mother was a Spanish mestiza who used to work as a cabecilla in a cigarette factory. His father, a tailor, had served as a teniente mayor of Tondo.26 Bonifacio was born in Tondo in 1863. The early death of his parents forced him to quit school in order to support his brothers and sisters. Bonifacio first earned his livelihood by making walking canes and paper fans which he himself peddled. Later, he worked as a messenger for Fleming and Co. and as a salesman of tar and other goods sold by the same firm. His last job before the Revolution was a bodeguero or warehouseman for Fressell and Company.