Richardson, Jim. "Andres Bonifacio in Cavite, April 24, 1897". (January 2006)

Introduction

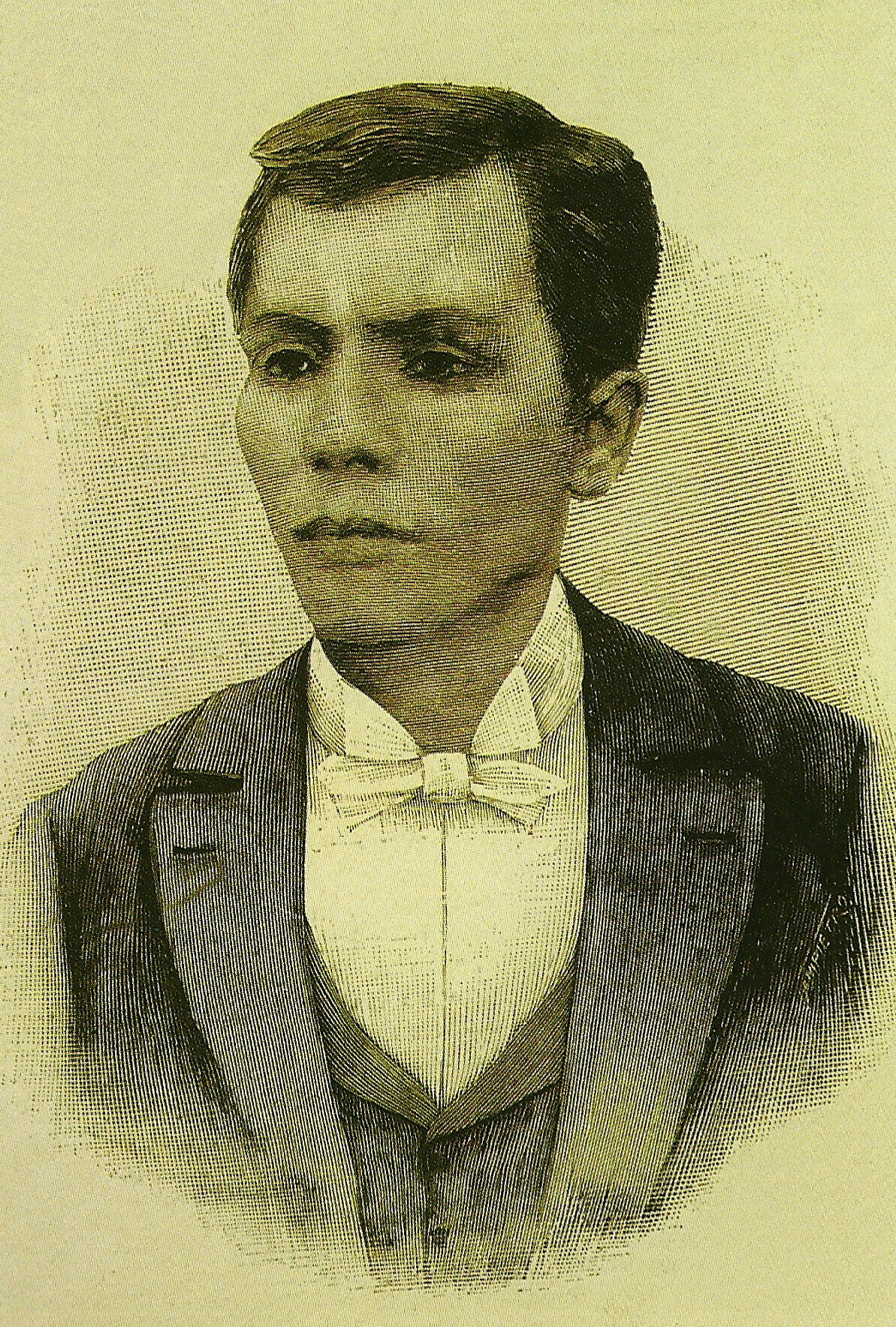

General Santiago Alvarez recounts in his memoirs that in early April 1897 Andres Bonifacio transferred his headquarters from the friar estate house in Naic to the barrio of Limbon, some twenty kilometers to the south in the municipality of Indang. He was accompanied "not only by his troops, but also by followers, men and women, old and young alike."1 Since late February, the Spaniards had been waging a successful counter-offensive against the insurgent forces in Cavite and by now had already recaptured several towns. Bonifacio’s personal authority as the leader of the Katipunan, meanwhile, had been devastatingly challenged by the momentous assembly held in Tejeros on March 22, at which a new revolutionary government had been created and Emilio Aguinaldo had been elected President. When Bonifacio moved to Limbon, says Alvarez, he was already planning finally to leave Cavite and journey north to the mountains above San Mateo, closer to Manila. For a while, though, Bonifacio and his followers set up a small fortified encampment in Limbon, and he remained there until his arrest by Aguinaldo’s soldiers on April 28. As is well known, he and his brother Procopio were then put on trial for plotting to assassinate Aguinaldo and overthrow the government. Found guilty, they were executed on May 10.

Read more »Introduction

General Santiago Alvarez recounts in his memoirs that in early April 1897 Andres Bonifacio transferred his headquarters from the friar estate house in Naic to the barrio of Limbon, some twenty kilometers to the south in the municipality of Indang. He was accompanied "not only by his troops, but also by followers, men and women, old and young alike."1 Since late February, the Spaniards had been waging a successful counter-offensive against the insurgent forces in Cavite and by now had already recaptured several towns. Bonifacio’s personal authority as the leader of the Katipunan, meanwhile, had been devastatingly challenged by the momentous assembly held in Tejeros on March 22, at which a new revolutionary government had been created and Emilio Aguinaldo had been elected President. When Bonifacio moved to Limbon, says Alvarez, he was already planning finally to leave Cavite and journey north to the mountains above San Mateo, closer to Manila. For a while, though, Bonifacio and his followers set up a small fortified encampment in Limbon, and he remained there until his arrest by Aguinaldo’s soldiers on April 28. As is well known, he and his brother Procopio were then put on trial for plotting to assassinate Aguinaldo and overthrow the government. Found guilty, they were executed on May 10.